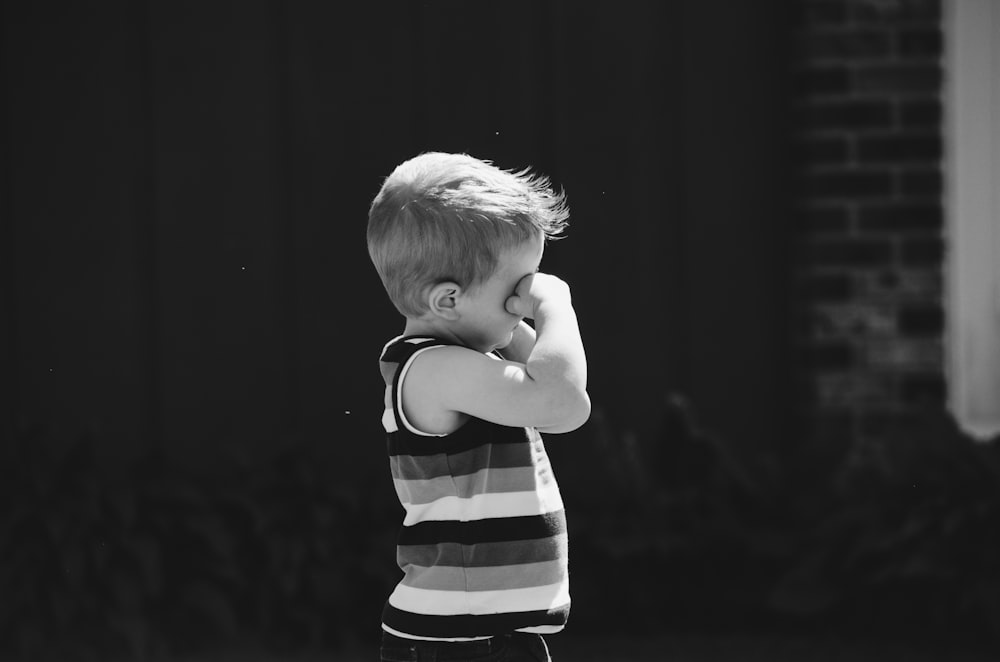

Grief; How you can support your child through it

These are tumultuous times. Perhaps some of the scariest many of us will live through. As adults, although this world scares us, we can make sense of it. We understand the rules we have to follow to keep safe, we know why everyone around us is so frightened and tetchy and we make allowances for that. We understand that deaths are occurring around us and we have our own understanding and coping mechanisms.

However, as a young child, our new world is confusing. There are things and places and people that have left our lives and they don’t always understand why. School is not the guaranteed routine anymore, playing and meeting friends cannot happen, maybe there is someone gone from their lives, who will not return.

Grief in children is a difficult thing to manage. Without being able to understand the ‘why’ of what happened, the situation and feelings can become overwhelming. So how can you help, as one of their primary care givers, to give them the support, closure and understanding that they need when grief needs to be felt?

If someone close to them is dying

This can be a time of immense stress. Children may not always understand exactly what is happening, but they can read the faces and atmosphere of the adults around them. The fear of the unknown is the worst enemy here, as it is this uncertainty that can really unsettle a child and make death all the more confusing.

The NHS suggests pre-bereavement counselling as a way of preparing the child for the loss they are about to experience. With an expert’s help, they can navigate the emotions and questions that come with experiencing a loved-one’s death. Another method of preparation for the death of a loved one is a memory box. If their loved one has been ill for a long time and death is something that the family is prepared for, if there is time, a memory box is a tool for closure further down the line. It provides an important link between the child and the deceased. If the death was unexpected, you and your child could make a memory box for the deceased, including your own memories and items.

If someone close to them has died.

Contrary to the instinct to protect the child by shielding them from what happened, the NHS suggests speaking openly – but sensitively – about the person who has died and the death that has occurred.

‘Direct, honest and open communication is more helpful than trying to protect your child by hiding the truth.’

It is also important to include them in any ceremonies or family events surrounding the death, for a sense of community mourning, inclusion and closure. It also allows them to avoid confusion about what has happened. Allowing the child to communicate their feelings, whether through games, photos, pictures, or whatever method they prefer also allows them to understand the death in their own way. When you are open about what happened, they will respond to that open channel of communication. To include the loss in their games or play as time goes on is perfectly normal.

If they are very young when the loss has occurred, it is something they may revisit over several years. This process may include emotional outbursts, such as anger or anxiety. Behavioural changes may also occur; they may withdraw from friends, have a changed eating or sleeping pattern or experience concentration loss or aggression. If these symptoms or others like self-blame for the death, self-destructive behaviour or desire to be with the person who died persist, then it maybe time to seek professional, specialised help.

Childhoodbereavment.ie provides this general guidelines chart to help you understand how your child is viewing the death that has occurred;

0-2 Years

After a death in the family it is common for a baby or toddler to become withdrawn or display outbursts of loud crying and angry tears. Although infants do not understand death, they know when things have changed, and may react to a person’s absence. This may show in clinginess and distress. Support them by maintaining the child’s routine and making them feel secure.

2-5 Years

The child still does not fully understand death. They don’t realise death is permanent and will happen to everyone. It’s important they know that they deceased is not simply ‘asleep’, and that they will not return. They may worry that something they said or did have caused the death, and need to be reassured that it wasn’t their fault. Children often ask the same questions over and over again. Support the child by encouraging them to ask questions, and answering them openly and simply.

5-8 Years

Children gradually learn that death is final and that all people will die at some time. This may make them worry that other people close to them will also die. It can help children to talk about these fears. We can’t promise children that no-one will ever die, but we can help them to feel safe by telling them that they will always be looked after. More curious children in this age group often ask direct questions about what has happened the body as they are trying to understand. They may blame themselves in some way for the death and can engage in ‘magical thinking’; filling the gaps when information has not been given to them. Support the child by encouraging them to talk about and express their feelings, no matter what those feelings are.

8-12 Years

This age group understands that death is irreversible, universal, and has a cause. Grief can express itself through physical aches and pains and challenging behaviour. It is important not to place unnecessary responsibility on children of this age; particularly eldest children who may feel responsible for younger siblings, or boys who lose their father and take on the role of ‘man of the house’. Support the child by reassuring them about changes in lifestyle (such as household income and the family home).

Adolescence

Adolescence is a time of great change. Teenagers struggle with issues of identity and independence as they try to bridge the gap between childhood and adulthood. Losing someone can make life very difficult.

Adolescents need clear and accurate information at the time of a death. Involving teens in the rituals can help them, but be sure to treat them in a manner appropriate to their age. They may wish to take an active part in funeral arrangements, or to mark the death in their own way.

Adolescents fully understand the concept of death. They know it is final and inevitable. However, confusion arises as they struggle with the many emotions, thoughts and mood changes that the death creates while trying to remain similar to their peers.

Children experiencing grief may experience many or none of these reactions. What remains important regardless of what form their grief take sis that channel of communication remains open, their questions are answered and that the death is spoken about.

For further questions, Childhoodbereavment.ie can be contacted here;

The Irish Hospice Foundation

4th Floor, Morrison Chambers

32 Nassau Street

Dublin 2

D02 YE06

T: 01 679 3188

E: icbn@hospicefoundation.ie